Excel VBA and Version Control

In our first post in this series, we described our motivation and strategy to address the technical debt in our Excel toolkit. Sometimes debt doesn’t reside just in a project’s code base, but also in its development process. A major challenge with writing VBA for an Excel add-in is version control. How do we track the changes to our VBA code and view the history of these changes when the add-in’s binary format does not play well with version control software?

Before the Unicorns team addressed this workflow, developers had to manually export VBA code from Excel’s Visual Basic Editor into *.bas text files. To make and record a code change, a developer directly edited the Excel add-in, manually copied the revised VBA code to a *.bas file, and then committed both the binary add-in and the source code text file. The downsides of this workflow are obvious:

- Because exporting each VBA module is a separate manual step, there’s strong incentive to minimize the number of modules. That does not lead to the best design architecturally.

- It’s clearly prone to human error. When a developer inevitably forgets to export a modified module, the add-in and the source code become out of sync in the repository.

We’re certainly not the first development team to face this challenge. A search on StackOverflow finds various approaches to address it. Many of them leverage the ability of an add-in to programmatically import and export VBA modules. Our solution also leverages this functionality, but combined with different modes of execution that we’ve introduced into our add-in.

Development and Production Modes

Our Excel add-in now runs in one of two modes: development or production. There are actually different copies of the add-in file, that correspond to these modes. Our revised development process has a naming convention to distinguish between these copies, which are called editions. This is illustrated with the sample add-in called “Simple Toolkit” in our excel-toolkit-framework project:

| Toolkit Edition | File Name | Menu Title |

|---|---|---|

| Development | Simple Toolkit_DEV.xlam | Simple Toolkit (dev) |

| Production (built) | Simple Toolkit_PROD.xlam | Simple Toolkit (prod) |

| Production (installed) | Simple Toolkit.xlam | Simple Toolkit |

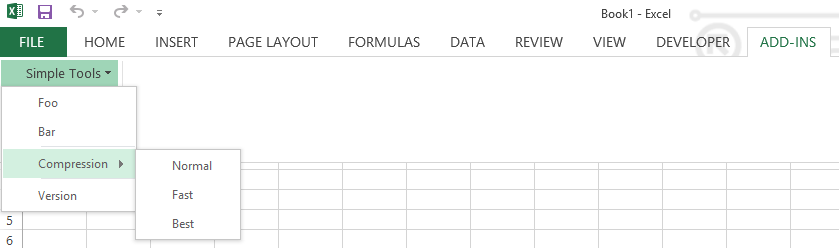

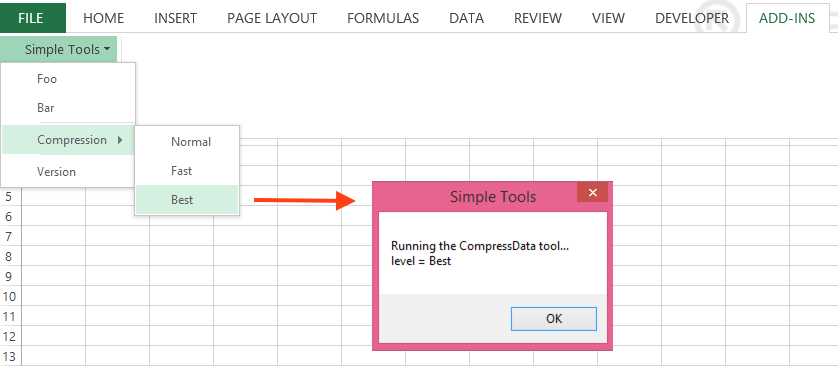

The Simple Toolkit’s menu is based on the example menu definition in the comments of the menu library module that we discussed in the first post.

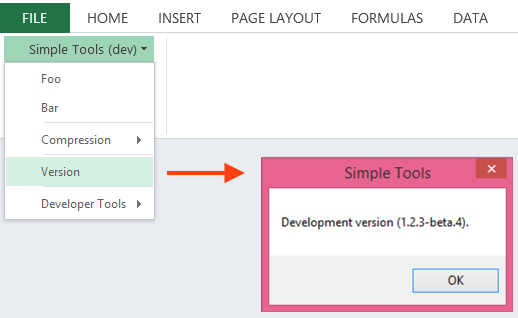

This sample toolkit is fully functional – each menu item simply displays a message box with the name of the selected item. For example:

A toolkit’s editions have different filenames because Excel cannot open 2 files with the same name even if they are in different directories. The different file names allow us to open multiple editions simultaneously for comparative testing. Therefore, we can have the latest production edition of an add-in installed on our systems while we work with the development edition to create the next release. The editions also have different menu titles to help us identify which edition we’re interacting with.

The naming convention distinguishes between the production edition of a toolkit that a developer has built in her workspace and the production edition once it’s been installed in the user’s add-ins folder 1. The different file names of these 2 copies control what their respective menu titles are.

Because the production edition is built by the development edition (we’ll cover the build process in a moment), the repository only contains the development edition, i.e., *_DEV.xlam. This is the file that developers work with.

Bootstrapping in Development Mode

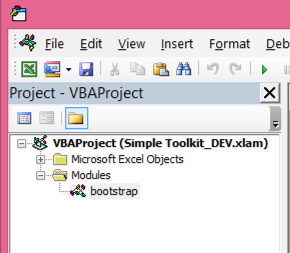

The development edition of a toolkit contains only one VBA module – this is what a developer sees in the VB Editor when she opens that edition with macros disabled:

The source code for that bootstrap module is in our excel-toolkit-framework project. The module has just one short procedure InitializeAddIn that’s called by the add-in’s Workbook_Open event handler. When any edition of the toolkit’s add-in is opened with macros enabled, that subroutine initializes the add-in as follows:

- Determine the mode from the add-in’s file name (if

DEVin the name, then mode = Development; else mode = Production). - If mode = Development, then dynamically load the toolkit’s other modules. (If mode = Production, then the modules are already in the production edition.).

- Call the

Initializeprocedure in the toolkit module which does the toolkit specific initialization (i.e., create its menu and any other necessary actions).

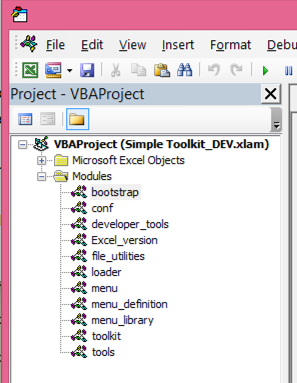

The bootstrapping of the development edition in step 2 is where the bootstrap module imports all the other VBA modules into the add-in programmatically. To accomplish this, the bootstrap module first imports these two modules:

- the toolkit’s corresponding configuration module, e.g.,

Simple Toolkit_conf.bas - the generic loader module

The configuraton module defines the constants for the toolkit’s configuration settings (i.e., its title, menu title, version #, etc.). One of those constants is a string with a list of VBA source files separated by vertical bars:

Public Const MODULE_FILENAMES = _

"excel_ver.bas" _

& "|file_utils.bas" _

& "|menu_lib.bas" _

& "|menu_defn_in_code.bas" _

& "|menu.bas" _

& "|toolkit.bas" _

& "|tools.bas" _

& "|dev_tools.bas"

The bootstrap module uses the loader module to import all the files in that list. Here’s the development edition of the Simple Toolkit with all its modules loaded:

In our improved development process, we’ve been able to reduce the VBA code stored in our Excel add-in to the bare minimum needed to bootstrap its development edition and to call the toolkit’s initialization procedure. That’s just 45 lines of code with comments included. All the rest of our VBA code base in now stored in VBA source files (*.bas) which are easily managed with version control software. This is a big win.

But what about the bootstrap module? Don’t we still need to manually export its source code from the VB Editor? Yes, but the module is very mature, so it rarely needs edited. And much more importantly, our toolkit now includes a convenient developer’s tool for exporting VBA modules.

Developer Tools

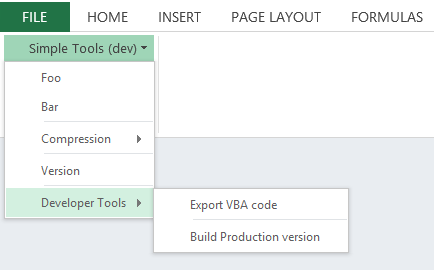

When our toolkit runs in Development mode, an additional submenu is available:

The menu is enabled using a clever technique to transform the lines of the menu definition after they’ve been loaded into a string array. By default, the submenu is disabled because its lines in the definition are commented out (recall from our first post that a comment line has a “#” as the first non-whitespace character):

Const MENU_DEFINITION_STR = _

"Foo | FooMacro" _

& vbLf & "Bar | BarMacro" _

& vbLf & "---------" _

& vbLf & "Compression ==>" _

& vbLf & " Normal | CompressData ""Normal""" _

& vbLf & " Fast | CompressData ""Fast""" _

& vbLf & " Best | CompressData ""Best""" _

& vbLf & "" _

& vbLf & "-------" _

& vbLf & "Version | DisplayVersion" _

& vbLf & "" _

& vbLf & "" _

& vbLf & "# (enabled only in Development mode)" _

& vbLf & "#dev>----------------------------------" _

& vbLf & "#dev>Developer Tools ==>" _

& vbLf & "#dev> Export VBA code | ExportVbaCode" _

& vbLf & "#dev> ------------------------" _

& vbLf & "#dev> Build Production version | BuildProductionVersion"

In Development mode, we scan the definition’s lines and remove the special prefix #dev> from each line. Stripping the prefix uncomments the lines, so the menu library module processes them to enable the submenu.

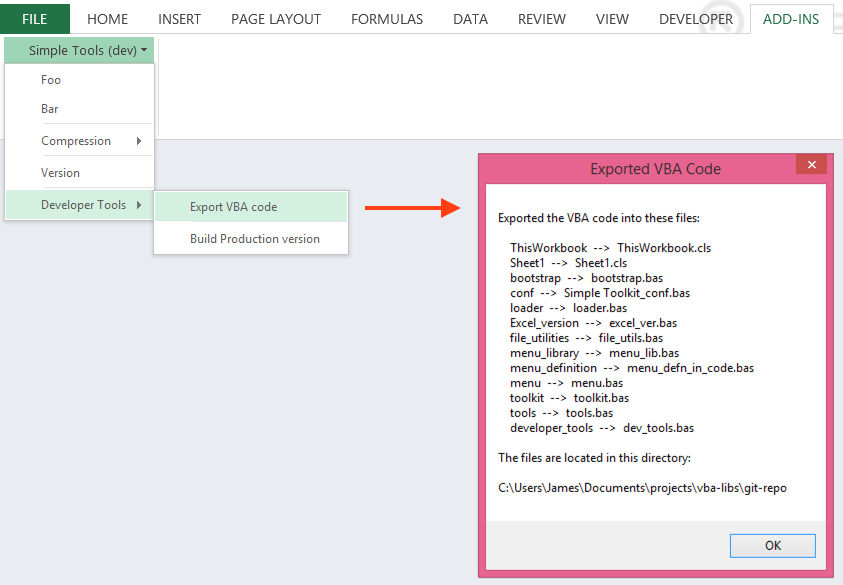

The first developer tool, Export VBA Code, exports all of the toolkit’s VBA source code in a single operation. Thus, with this tool, a developer can edit code in various modules directly in the VB Editor, and then export the modules, so the changed code will be loaded the next time that the development edition is opened.

Note: the source code files for all of the add-in’s VBA components are exported. So, not only are all the standard VBA modules exported, but so are the add-in’s event handlers (the latter are exported into the class module ThisWorkbook.cls). Therefore, we can view the revision history for all of our add-in’s VBA code base in version control.

Another huge gain with this dynamic bootstrapping is that a developer is no longer restricted to the VB Editor for editing code. She can use her favorite text editor to modify the *.bas files (Notepad++, SublimeText, vim 2, etc.), and then open the development edition to load and test the changes.

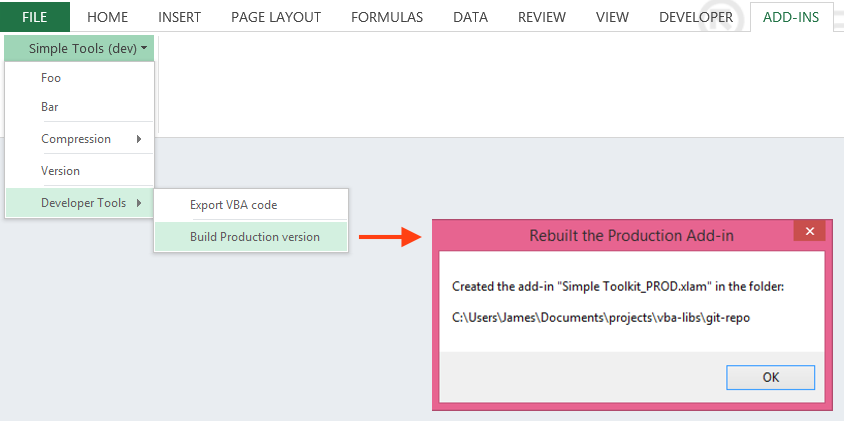

Build Process

Once a developer is satisfied with her code changes, she builds the production edition of the toolkit using the Developer Tools:

The development edition creates the production edition by saving a copy of itself with the corresponding production file name (e.g., Simple Toolkit_PROD.xlam). Because the development edition loads all the VBA modules during initialization, the modules are saved in the production copy. Since the production copy contains the modules, no bootstrapping is needed when it’s opened.

When saving a production copy, the development edition stores the current time as the build’s time stamp, and inserts the toolkit’s version number into a couple file properties.

Build Date

An Excel add-in is actually a special type of workbook. Because every workbook must have at least one worksheet, an add-in has a single worksheet that’s hidden. This hidden worksheet is where the development edition stores the build’s time stamp before saving a production copy.

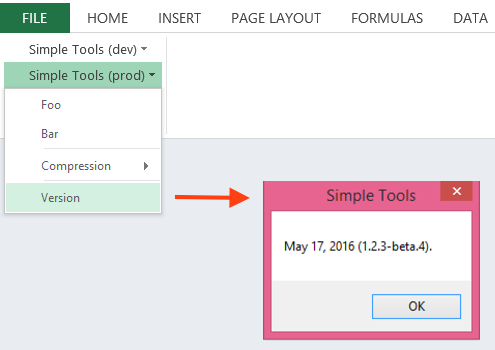

When the production edition is opened and initialized, its build date is extracted from the stored time stamp. With the toolkit’s menu, the build date can be displayed along with the version number:

Previously, developers had to set the build date manually during the release process. This error-prone manual step has now been automated in our new build process. Because the development edition doesn’t have a build date, there is none in its version message:

Version Number in File Properties

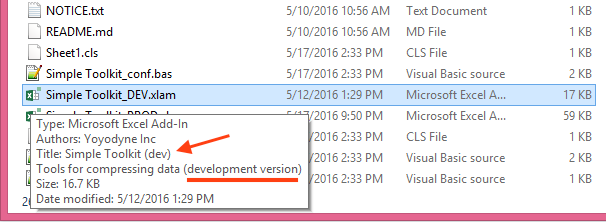

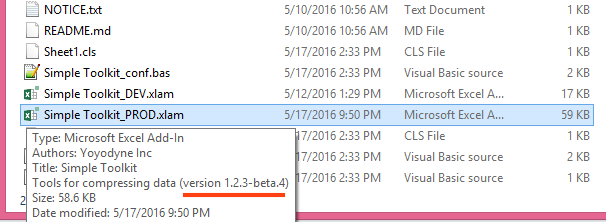

Using instructions based on the ones provided by Chip Pearson, we can set various file properties of the development edition. In particular, we put special markers in the Title and Comment properties:

When the production edition is built, the (dev) marker is removed from its Title property, and the development version marker in its Comments property is replaced with the toolkit’s version:

So our build process ensures that regardless of where a toolkit’s add-in is copied or how it’s renamed, we can always determine the edition and version of each copy.

If You Build It, Python Will Come

Wow, quite a lot to digest here! Over the course of this article, we’ve described how we’ve tranformed a monolithic VBA code base into a nicely modular set of files. We’ve setup a version control-friendly bootstrapping process in which only a small piece of mature code needs to be included in the add-in, with the rest loaded in dynamically. We’ve developed a tool for exporting code from the VBA editor directly to source files, eliminating ham-handed copy-paste workflows. Finally, we’ve produced a robust build process that handles both Developer and Production editions, automatically taking care of proper file naming and timestamping, and providing a huge improvement in development cycle time.

But what about Python? Wasn’t the whole purpose of this journey to get from VBA-powered Excel macros to Python-powered Excel macros? YES! All of these steps were necessary in getting an antiquated system out of the 1990s and poised for a smart and maintainable environment suitable for Python macros. Our next posts will cover the final hoops in linking our framework up to Python using xlwings and Miniconda.

Acknowledgements: Ben Klaas contributed to this article.

Update on 2016 Sep 28 – Replaced the link to Chip Pearson’s instructions with a link to extended instructions in the excel-toolkit-framework wiki.

Update on 2020 Mar 6 – Updated the links to our excel-toolkit-framework project for the repository’s new name.

Authored by Jimm Domingo

Code · Infrastructure

IPUMS Excel VBA UnicornRainbows