Towards a Sustainable Excel

This is the third post in our Unicorn Rainbow series. In previous posts, we examined Excel menu creation and handling version control in VBA and Excel. In this article, I will describe how we incorporated Python into our Excel toolkit.

Up With Python, Down With VBA

Excel macro development will cause shudders amongst developers. While VBA is an antiquated language not even Microsoft recommends using, there is an option outside of a bulky .NET solution: Python.

Historically, Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) was the only option for writing macros in Excel. Microsoft now recommends using .NET for Applictions; however, for software teams that are otherwise focused on open-source languages, like Python, this is a solution that carries a lot of overhead. Using Felix Zumenstein’s excellent Python-to-Excel library and bridge technology xlwings, it is now possible to develop Excel macros in Python.

Why Python?

Any “why this language” discussion can be contentious for a variety of valid and not-so-valid reasons. In our case, Python is a great choice because:

- The Excel-to-Python link is already implemented, and readily available.

- We have in-house Python expertise.

- Iterating and debugging Python is much quicker than VBA. Much. Quicker. You can attach a dollar figure on that but it has the added benefit of leaving work with a smile and an unclenched jaw.

- It eliminates the need to use the archaic VBA editor to debug things. I now develop in my editor of choice and see changes to my dev code simply by re-running the Python-based macro. No Excel restarts. No VBA version control conundrums.

- Our behind-the-scenes data processing code runs on Linux and heavily leverages Python. Furthermore, we use in-house metadata Python libraries to efficiently harvest information by reading spreadsheets into Pandas dataframes. Having those libraries also usable on Windows via Python-based Excel macros is HUGE for us.

Xlwings Helps You Fly

In order to call Python in Excel, a bridge technology is needed. There are a few different solutions for this problem, including PyXLL and DataNitro. After evaluating our options, we settled on xlwings. It had a few advantages over competing technologies:

- xlwings is callable from outside Excel. Of particular interest is the ability to interact with Excel inside Jupyter Notebooks. So while creating Python-based Excel macros was our primary goal, this added bonus was a big deal.

- We like free and open-source software, and xlwings is both.

- We liked the relatively clean API xlwings provides for interacting with Excel workbooks.

Getting xlwings running inside Excel at a superficial level involves adding a xlwings.bas file that xlwings provides. In our implementation, there’s a little more to it than that, but beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say, xlwings has the link covered.

Putting xlwings Into Action Via Our PythonTool Architecture

One of the things engineered into the Excel menu creation technique described in our previous post was the ability to fork any menu item action off to either VBA or Python. The way we do this is by specifying any particular item with the PythonTool macro. PythonTool is a VBA procedure that calls xlwings’ RunPython macro with a Python code snippet that includes the string name of the tool we want to run. For example:

Hello World | PythonTool "hello world"

will call RunPython for the tool we’ve implemented in Python as “hello world”.

In our Python codebase, we have a dictionary that translates these strings into specific tool classes.

TOOL_CLASSES = {

"batch": batch.FileBatchTool,

"batch - new list": batch.NewListTool,

"no-op": tool_base.PythonTool,

"hello world": HelloWorldTool,

"toolkit info": ToolkitInfoTool,

"display ipums-metadata version": ToolkitMetadataTest,

"export dd control file": export_csv.ExportThisDDSvarsCsv,

"export all control file data": export_csv.ExportAllDDSvarsCsv,

"export control file": export_csv.ExportControlFileCsv,

"xlwings test": export_csv.XlwingsTest,

"create output data type column":

data_dictionary_manipulate.CreateDataTypeColumn,

}

So, when a user in Excel selects the menu item labelled “Hello World”, the PythonTool macro is called with the name “hello world”, which in turn, runs the HelloWorldTool in Python. Here is the code for that class:

class HelloWorldTool(tool_base.PythonTool):

PROMPT = 'What is your name?'

TITLE = 'Your name'

DEFAULT_NAME = 'World'

GREETING = 'Hello {}'

def run(self):

name = self.add_in.input_text(HelloWorldTool.PROMPT,

HelloWorldTool.TITLE,

HelloWorldTool.DEFAULT_NAME)

if name is not None:

self.add_in.msg_box(HelloWorldTool.GREETING.format(name))

And here it is in action…

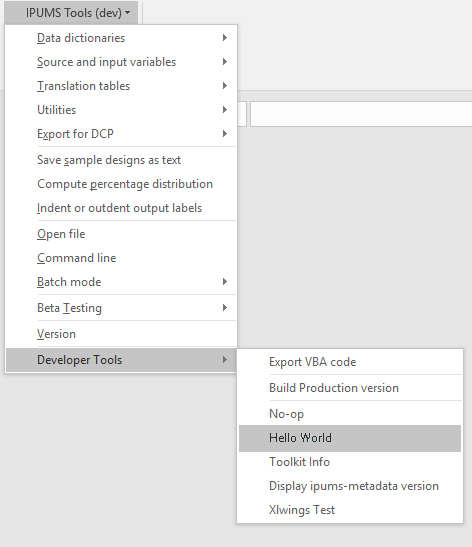

The menu:

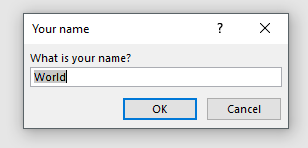

The input_text add_in:

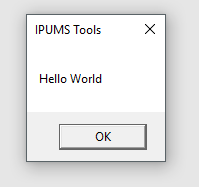

And finally the msg_box. Hello World!:

Every PythonTool has access to some common functionality that we’ve engineered via the add_in object. This allows for reusable Excel-side widgets like message boxes for both text input and information (as seen in the hello world tool code above), creating new workbooks, even spinning the cursor while a process is running.

That’s the HelloWorld example, but obviously we want to do much more than this, and we already have. For example, we have a need to export some specific structured data from a large set of workbooks. The exports are done periodically and only need to be done if the workbook itself has been updated since the last export. I wrote a PythonTool that systematically:

- Goes through the workbook list, determines which workbooks need export (through file mtime comparison).

- Those workbooks that need export are then read into Python using the Pandas library.

- Once the workbook is in a Pandas data frame, the necessary data are gathered and exported.

- Meanwhile, the PythonTool opens a report workbook that shows the real-time progress of each workbook export.

I can’t emphasize this enough, this is SUCH an improvement over writing VBA. Faster to write. Faster to execute. Easier to maintain.

But Wait! There’s More!

I’ve described a lot here, but there are more topics to cover in future posts. Here are some teasers:

- Python environment support with conda and conda-build

We have an in-house Python library that is specifically designed for harvesting information from the large set of Excel metadata workbooks we develop here. The library itself is in active development, is cross-platform and has a broader use than just our Excel-Python environment. Using conda and conda-build, we maintain a custom conda channel for making in-house libraries capable of simple installation and use by end users. Further, we deliver a custom conda environment as part of the end-user installation of the Python-powered Excel macros, and that environment automates the installation of our in-house library (as well as anything else we need outside of Python’s stdlib: pandas, numpy, xlwings, etc.)

- Remote process execution

Though Excel macros are now much more efficient by using Python, at MPC we often have processes that require extra computing power. Our next generation PythonTools will farm jobs off to a linux compute cluster and report back results rather than doing the processing locally on Windows machines.

Acknowledgements: Jimm Domingo contributed to this article.

Authored by Ben Klaas

Code

IPUMS Excel VBA Python UnicornRainbows