Big Data on a Laptop: Tools and Strategies - Part 2

Introduction

Doing analysis on big data doesn’t have to mean mastering enterprise Big Data tools or accessing hundred-node compute clusters in the cloud. In this series, we’ll find out what your humble laptop can do with the help of modern tools first.

In the first part of this series, we looked at how to get out of Excel and work with big datasets more effectively. We found an easy way to query CSV data, but performance degraded quickly as data size increased and memory requirements became prohibitive. Today, we’ll look at Parquet, a columnar file format that is optimized for space and makes it easier and much faster to extract subsets of the data.

Part 2 is a Bit of a Slog…

Before we start, I want to give notice that this post is going to be a bit dense. Not only is it unusually long, it’s also extra heavy on the technical detail. The technologies we’re talking about today were originally intended to be used within the Apache Spark cluster computing environment. When used in that manner, a lot of the detail is abstracted away under the hood. Today, we’re going to be using some of these components in a standalone laptop environment instead, which requires that we get our hands pretty dirty.

We’re going to be showing some pretty detailed operations, both in C++ and Python. They’re not for everyone, but for those who are proficient with C++ or Python and need to work with big data on small machines, the techniques we’ll present today can be transformational for your workflow.

For everyone else, stay tuned for Part 3. That’s when we’ll show how to run Spark on your local machine, which hides a lot of the detail we’re covering today.

Save Space and Time with Columnar Data Formats

Recall that we were working with a large commuting patterns dataset with 82 variables in it. If we can avoid loading the entire example dataset into memory, we’d be able to analyze much larger datasets given the same hardware. For instance, in the last query from the earlier post, we only needed to examine four columns out of 82.

Columnar file formats address this use case head-on by organizing data into columns rather than rows. Such a structure makes reading in only the required data much faster. In simple terms at the low level, a reader seeks to the start of a column’s worth of data in the data file, then reads until the indicated end location of that column in the file. Columns of data not requested never get read, saving time. To make reads even faster, and to save space on disk, columnar formats typically use data compression on a per-column basis, which often makes the compression algorithms more effective than with row-based data while preserving relatively high-speed decompression.

Parquet

Parquet is a columnar storage format for data used in Apache products like Spark, Drill and many others. It compresses to impressively high ratios while enabling super fast analytic queries. In many cases you win both in huge storage savings and dramatically lower query times. For the following examples consider Parquet files as extremely high performance, strongly typed versions of CSV files.

It’s also helpful to be aware of Apache Arrow. Apache developed Parquet to be a columnar storage format. Concurrently, they developed a product called Arrow which is a cross-language platform for columnar in-memory data. Parquet and Arrow are meant to work together to create a highly performant and efficient data layer. You’ll see some references to Arrow in the Python examples later on. (Aside: I’ve written more extensively about Arrow on my personal blog).

Here I’ll demonstrate use of the Parquet data format in a command-line tools setting, using both C++ and Python. While typically coupled with big data tools, you can also use Parquet libraries with your own code to build a command-line data analysis workflow. While we saw in Part 1 that the size of my example dataset is just on the edge of what’s possible to fit in a typical laptop’s memory, we can still benefit with performance and space savings by converting to Parquet. If the data were ten times larger (easily possible if all available IPUMS U.S. Census data were used) a columnar, compressed format like Parquet would be absolutely necessary to work with it on a laptop or desktop.

parquet-cpp - A C++ Library for Parquet Data

Thanks to the parquet-cpp project you don’t need to set up a big data execution framework like Spark just to use Parquet. The following examples achieve good performance by direct use of the C++ Parquet library. (There are Parquet libraries for other languages too, including Go and Java. There’s also Parquet library support for Python, which we will explore later in this article.)

Memory use by parquet-cpp will be exactly proportional to the number of columns involved in a query. Some queries can be optimized further by aggregating data as columns are read in (averages, counts) while others require complete column data to compute (e.g. medians). With 17,000,000 rows and four columns our example will require at most 259 megabytes (17000000 * 4 columns * 32 bit number types). This means we could work with a Parquet dataset with up to around 525,000,000 rows on an 8GB laptop, larger than the entire population of the U.S., before even attempting to optimize for memory use.

Converting Data to Parquet with C++

The first thing we need is a way to create Parquet data. To create Parquet-formatted data, you can write your own utility using one of these Parquet language libraries. C++ will be most efficient both with memory and CPU usage but perhaps another language will be more convenient depending on your preferred language. For work here at IPUMS I have written a stand-alone tool, make-parquet, in C++ for converting either CSV or fixed-width data (another of the IPUMS data formats) to Parquet format. It’s very fast and minimizes memory use; you can easily run it on your laptop.

Below is a bit of what the make-parquet program looks like. When I began writing C++ tools to handle Parquet-formatted data the low-level API was the only interface to the library, so that’s what I used to make make-parquet.

In essence the parquet-cpp library gives you:

- parquet types to group together into a schema

- parquet::FileReader

- parquet::FileWriter

- parquet::RowGroupReader

- parquet::RowGroupWriter

- parquet::ColumnReader

- parquet::ColumnWriter

You call ColumnReader::ReadBatch() and ColumnWriter::WriteBatch() to actually move data in and out of Parquet files; compression gets handled by the library as well as buffering. Once you’ve extracted data from a data source, say a CSV or fixed width text file, the core of the “make-parquet” program looks like:

// Handles int32 and string types; you could extend to handle floats and larger ints. by

// adding and handling additional types of buffers.

//

// The new high level interface supports a variant type that would allow you to pass all data

// buffers as a single argument...

//

// To avoid one argument per data type, you could instead defer conversion from raw string

// data until right before sending to WriteBatch(). However this means that buffering a single

// untyped, optimally-sized row group in RAM requires much more space; perhaps four to five times as much.

// You'd soon run out of memory before running out of CPU cores on most systems...

//

// The perfect solution in terms of RAM would be to know in advance exactly how many row groups you will

// consume and their sizes, removing the need to buffer at all; but that would necessitate scanning the

// input data in advance to compute row group sizes, which is time-consuming on its own. This is all a

// result of needing to set the row group size before writing to the row group.

static void write_to_parquet(

const std::map<int, std::vector<std::string>> & string_buffers,

const std::map<int, std::vector<int32_t>> & int_buffers,

std::shared_ptr<parquet::ParquetFileWriter> file_writer,

int row_group_size,

const std::vector<VarPtr> & output_schema){

// Create a row group in the parquet file, The row group size should be rather large

// for good performance, so that row_group_size * columns == 1GB

parquet::RowGroupWriter* rg_writer =

file_writer->AppendRowGroup(row_group_size);

// Need to loop through columns in order; order of the output_schema matters therefore.

for (int col_num=0;col_num<output_schema.size();col_num++){

// Grab the description of a column

auto var = output_schema[col_num];

// Figure out the type of data and where to get it from

if (var->type ==parquet_type::_int ){

auto column_writer=

static_cast<parquet::Int32Writer*>(rg_writer->NextColumn());

auto & data_to_write = int_buffers.at(col_num);

column_writer->WriteBatch(

data_to_write.size(), nullptr, nullptr, data_to_write.data());

}else if (var->type == parquet_type::_string){

// This is how UTF-8 strings are handled at the low level

auto & data_to_write =string_buffers.at(col_num);

auto column_writer = static_cast<parquet::ByteArrayWriter*>(rg_writer->NextColumn());

for(const std::string & item:data_to_write){

parquet::ByteArray value;

int16_t definition_level = 1;

value.ptr = reinterpret_cast<const uint8_t*>(item.c_str());

value.len = var->width;

column_writer->WriteBatch(1, &definition_level, nullptr, &value);

}

}else{

cerr << "Type " << var->type_name << " not supported." << endl;

exit(1);

}

}

}

You can see this is definitely a low-level API. The newer high-level API (not discussed here today - it wasn’t available when I was writing make-parquet) would make this process much friendlier. Nevertheless, it may be helpful to see how the data is converted to Parquet.

The conversion process takes around five minutes with my make-parquet utility for the example usa_00065.csv dataset.

Here’s the dataset from the last section before and after converting to Parquet:

$ ls -sh usa_00065.csv

4.2G usa_00065.csv

After converting usa_00065.csv to a parquet version named usa_00065.parquet using default “snappy” compression:

$ ls -sh usa_00065.parquet

688M extract65.parquet

See how small it got? That’s just one of the benefits. Watch how fast it goes.

Working with Parquet Data in C++

First, going back to our q example that used CSV data:

$ time q -d, -b -O -D"|" -H \

"select YEAR, \

sum(case when TRANWORK>0 then PERWT else 0 end) as trav_total, \

sum(case when TRANWORK=40 then PERWT else 0 end) as bikers_total \

from ./usa_00065.csv \

where OCC2010<9900 and YEAR > 1970 \

group by YEAR"

YEAR|trav_total|bikers_walkers_total

1980|94722000 |5385300

1990|114747377 |4931475

2000|128268633 |4244613

2010|137026072 |4515708

2016|150439303 |4932296

real 24m38.919s

user 24m18.680s

sys 0m20.048s

We recall this took almost 25 minutes. Now let’s see how Parquet can dramatically improve upon this. But before we get there, we have to solve a new data format problem we just created. Recall that the q program needs CSV-formatted data as input. Now that we’ve converted to parquet, we’ll need to do something to get back to CSV first before we can use q. That something in my case is a custom utility I wrote called tabulate_pq.

tabulate_pq - a C++ Parquet tabulator

Note: if C++ isn’t your thing, hang tight. I’ll eventually explain how to do this in Python, too.

tabulate_pq is a C++ program that demonstrates one simple but powerful use of a specialized Parquet reader: weighted cross-tabulations. The program takes a Parquet file, a weight variable (or ‘1’ if no weight variable is present, indicating each record refers to an actual case), and up to three column names to cross-tabulate. For readers who are not familiar with cross-tabulations, the concept is straightforward: if you are cross-tabulating two variables, say AGE and SEX, you’ll end up with a value (aka “cell”) for each possible combination that represents the count of records that have that combination: for instance, there will be a value for “1 year old males”, another for “1 year old females”, a third for “2 year old males”, and so on, for every combination of age and sex.

tabulate_pq computes these cross-tab cells and then outputs the result as a CSV-formatted table to standard out. Let’s see an example.

$ tabulate_pq ./extract65.parquet YEAR OWNERSHP

YEAR,OWNERSHP,total

1960,0,4903864

1960,1,112060391

1960,2,62328797

1970,0,5823600

1970,1,131963200

.....

Here we have a YEAR variable (representing census year) and an OWNERSHP variable which has three possible values for the person’s home ownership status: 0 = N/A, 1 = owned, and 2 = rented. Here in tabulate_pq’s CSV output we can see that for example that in 1960, 112 million people lived in a home owned by themselves or a relative.

There’s more to tabulate_pq than we show here in this code snippet, but to give you an idea of how tabulate_pq leverages the parquet-cpp library, here’s a sample of the core of the program:

// Suppose we can determine the column indices to

// extract by matching column names in the schema

// with their positions....

vector<int> columns_to_tabulate = get_from_schema("{"PERWT",AGE","MARST"});

// Can extract columns in parallel

reader->set_num_threads(4);

int rg = reader->num_row_groups();

// You can read into a table just a group of rows

// rather than the entire Parquet file...

for(int group_num=0;group_num<rg;group_num++){

std::shared_ptr<arrow::Table> table;

reader->ReadRowGroup(rg, columns_to_tabulate, &table);

auto rows = table->num_rows();

vector<const int*> raw_data;

// We pull out a list of pointers to raw data so that

// we can produce an arbitrary length record as long as

// the data type is known up-front. This way we can support

// tabulating one, two, three, four or even more columns.

for(int c=0;c<columns_from_schema.size();c++){

auto column_data = std::static_pointer_cast<arrow::Int32Array>(

table->column(c)->data()->chunk(0));

raw_data.push_back(column_data->raw_values());

}

// There is an experimental API in the works to automate conversion

// from columnar to record layouts, but for now it's manual ...

for(int row_num=0;row_num<rows;row_num++){

vector<int32_t> record;

for (int c=0;c<columns_to_tabulate.size();c++){

auto datum = raw_data[c][row_num];

record.push_back(datum);

}

// First column is assumed to be weight, the rest get crossed

// with each other and the counts weighted.

add_to_tabulation(record);

}

}

The concept of row groups is important. If you’re memory constrained you may need to read in one row group worth of a column at a time as we do in the example above (these are known as column chuncks.) This way you can read in part of a column, deal with the data by performing some reduce operation and dispose of the memory before moving on to the next row group.

tabulate_pq is a useful utility in it’s own right, but remember that we were doing this so that we could get back to CSV input for our q CSV querying program.

q Revisited

Now that we have a way to get Parquet data back into CSV format, let’s see how we can query Parquet data with q. Here’s our 25-minute example, this time starting from Parquet data and using our tabulate_pq program as a helper to make the CSV data for q.

$ time ./tabulate_pq ./usa_00065.parquet PERWT YEAR TRANWORK OCC2010 | \

q -d, -b -O -D"|" -H "select YEAR, \

sum(case when TRANWORK>0 then total else 0 end) trav_total, \

sum(case when TRANWORK=40 then total else 0 end) bikers_total \

from - \

where OCC2010<9900 and YEAR > 1970 \

group by YEAR"

** Diagnostic output of tabulate_parquet **

num_rows: 17634469

file has 8 row groups.

Data extract took: 1.437 seconds.

Cross tab computation took: 1.027 seconds.

** Output of q **

YEAR|trav_total|bikers_walkers_total

1980|94722000 |5385300

1990|114747377|4931475

2000|128268633|4244613

2010|137026072|4515708

2016|150439303|4932296

YEAR|trav_total|bikers_total

1980|94722000 |446400

1990|114747377|461038

2000|128268633|485425

2010|137026072|726197

2016|150439303|861718

real 0m2.212s

user 0m1.859s

sys 0m0.375s

Well, that was super fast!! 25 minutes is now down to 2 seconds. That’s a 750x speedup. Not bad!

Let’s take a closer look at what I did there. The q program is attached to tabulate-pq by a UNIX pipe. So, tabulate_pq processes the Parquet and outputs the CSV-formatted cross-tabulation, which is piped to the next program, q. If we select from - in our from clause, q reads from standard input on the command line. Perfect!

We have off-loaded the expensive I/O to an efficient format and fast program. Since the output of tabulate_pq is tiny compared to the dataset itself, we can efficiently pipe the output right to q for final processing. Any analytical sum or count query involving three or fewer variables can be done in this way using my tabulate_pq helper script. If I were seriously pursuing this approach, I might extend tabulate_pq to allow many more variables and handle multiple file Parquet datasets.

Digging Deeper into our Commuting Data

Now that we have a fast way to query the data, it’s easier to iterate over our dataset, asking more interesting questions. We can look at tech workers in more detail without having to run the query over lunch. I’ve added other categories of transportation to the original query to see how tech workers compare to the average worker in every mode of transit:

$ time ./tabulate_pq ./usa_00065.parquet PERWT YEAR TRANWORK OCC2010 | \

q -d, -D"|" -b -O -H \

"select sum(TOTAL), case \

when OCC2010/100 = 10 then 'programmer' else 'other' end as programmer, \

case when TRANWORK=0 then 'N/A' \

when TRANWORK=40 then 'biker' \

when TRANWORK/10=3 then 'public' \

when TRANWORK/10 = 1 then 'car' \

when TRANWORK=50 or TRANWORK=70 then 'walk_or_home' \

else 'other' end as travel \

from - \

where YEAR=2016 and TRANWORK>0 and OCC2010 < 9900 \

group by travel,programmer

** Diagnostic output of tabulate_pq **

num_rows: 17634469

file has 8 row groups.

Data extract took: 1.238 seconds.

Cross tab computation took: 0.836 seconds.

** Output of q **

sum(TOTAL)|programmer|travel

824999 |other |biker

36719 |programmer|biker

125432749|other |car

3020400 |programmer|car

1569042 |other |other

40017 |programmer|other

7493340 |other |public

374745 |programmer|public

11098514 |other |walk_or_home

548778 |programmer|walk_or_home

real 0m2.189s

user 0m1.984s

sys 0m0.219s

We could look at the relative rates between tech workers and other workers for each mode of transit to see if tech workers seem to choose certain modes of transportation more often than the working population as a whole. But it’s starting to get hard to make sense of all of these numbers on the command line, so let’s see if we can make this a bit more visual.

Add Visualization to the Pipeline with GnuPlot

I’d like to start exploring commuting patterns by income level, but the results of this next query would be overwhelming to read in a table. I’ll need to create a bunch of income brackets, too many to easily read in a table. So I’ll graph the data with GnuPlot instead.

I’m wondering what leads people to choose human-powered (bike or walk) transport to work. Maybe the higher rate of bike commuters among tech workers is a reflection of their relatively high incomes, or maybe they are outliers and rates of non-car commuting are actually higher at lower incomes because cars cost more money. We’ll soon find out. I’ll ignore work-from-home people (not commuting at all) and public transportation (just to simplify things) for this example.

Here I’m gluing a script together with the shell and passing all commands to GnuPlot on the command line. It’s a great approach for exploring data, but once you’ve found the interesting plots you’ll likely want to explore gnuplot some more with a dedicated script.

You can control the output format, labels, graph styles and really anything about the graph. The >cat indicates data will come from standard input rather than a file; to plot data from a file instead you’d write something like gnuplot -e "plot 'results.tsv'".

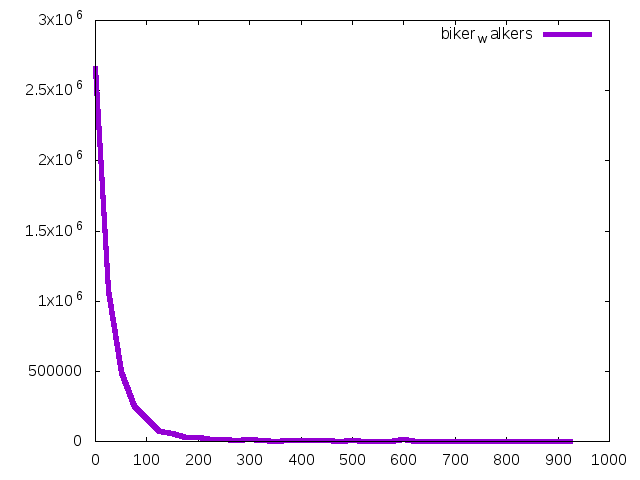

$./tabulate_pq usa_00065.parquet PERWT YEAR TRANWORK INCTOT |

q -d, -H -O "select ((inctot/25000)*25000 / 1000) || 'K' as income, sum(total) as biker_walkers \

from - \

where YEAR=2016 and tranwork in(40,50) and INCTOT>0 and inctot < 990000 \

group by inctot/25000 \

order by inctot/25000 desc" |

gnuplot -e "set terminal png;set style data lines;\

set datafile separator comma;\

plot '< cat' title columnheader linewidth 5" > count_bikers_walkers_by_income.png

We pipe the table made by q to gnuplot for graphing. Our command makes this graph:

Income in thousands is on the X-axis, numbers of human-powered commuters is on the Y-axis. Pretty much looks like an income distribution; of course the vast majority of anybody doing most things is on the lower income side (by a lot.) We’re not learning much yet. Instead we should compare percent of bikers and walkers within each income bracket. There may be many fewer people biking who earn $150,000, but what’s the ratio of drivers to walkers and bikers at each income bracket? I’m cutting off the income at $400,000; there are too few cases in the sample to get much accuracy at higher income levels.

$ time ./tabulate_pq usa_00065.parquet PERWT YEAR TRANWORK INCTOT |

q -d, -H -O "select ((inctot/20000) * 20000)/1000 as income_thousands,sum(case when tranwork in (40,50) then TOTAL else 0 end) * 100.0 / sum(TOTAL) as bike_or_walk \

from - \

where YEAR=2016 and INCTOT>0 and inctot < 400000 \

group by inctot/20000 \

order by inctot/20000 desc" |

gnuplot -e "set terminal png;set style data lines;\

set datafile separator comma; \

plot '< cat' title columnheader linewidth 5" > percent_bikers_walkers_by_income.png

real 0m5.051s

user 0m5.031s

sys 0m0.766s

In this plot the X-axis is income in thousands, the Y-axis is percent of total commuters who bike or walk.

Returning to our original inquiry about biking to work – are tech workers special, or is there a higher rate of biking to work at moderately high incomes compared to median income and below?

$ ./tabulate_pq usa_00065.parquet PERWT YEAR TRANWORK INCTOT |

q -d, -H -O "select ((inctot/20000) * 20000)/1000 as income_thousands,sum(case when tranwork in (40) then TOTAL else 0 end) * 100.0 / sum(TOTAL) as biking \

from - \

where YEAR=2016 and INCTOT>0 and inctot < 400000 \

group by inctot/20000 \

order by inctot/20000 desc" |

gnuplot -e "set terminal png;set style data lines;\

set datafile separator comma; \

plot '< cat' title columnheader linewidth 5" > percent_bikers_by_income.png

So it appears biking increases a lot as income rises, and it’s interesting to note the two spikes on both graphs of bikers and walkers and bikers. Notably, walking among low income people drops off sharply as income increases, while biking goes in the other direction. Overall, we can see the higher rate of biking among tech workers is in line with everyone else earning similar incomes ($70,000 to $160,000).

To be clear, all we’ve seen so far are some interesting corelations; we could include a number of additional variables to tease out connections between occupation, income and lifestyles. The point here is that this sort of tool chain makes it easy to iterate quickly, testing different hypotheses and rapidly analyzing the data from multiple angles as we refine our inquiry.

Parquet with Python: PyArrow

As promised, it’s time to discuss how we can do the same thing in Python as I showed above in C++.

The Python binding to Parquet and Arrow is known as PyArrow. With PyArrow, you can write Python code to interact with Parquet-formatted data, and as an added benefit, quickly convert Parquet data to and from Python’s Pandas dataframes. Pandas came about as a method to manipulate tabular data in Python. It tries to smooth the data import / export process and provide an API for working with spreadsheet data programmatically in Python. It’s essentially an alternate approach to the problem the q utility tries to solve, though Pandas does much more.

Chances are if you’re working in Python with a lot of data, you already know of Pandas, but if not, it’s a great resource! However, large datasets have long been problematic with Pandas due to inefficient memory use, and reading large data could be faster than it is with Pandas. That’s where PyArrow enters the picture. PyArrow is based on the “parquet-cpp” library and in fact PyArrow is one of the reasons the “parquet-cpp” project was developed in the first place and has reached its current state of maturity.

Let’s test a similar query to the previous example queries, this time using PyArrow and Pandas. First though, we need to install them. The following code will install in Python 2 by default if that’s your system Python; but it will install into Python 3 as well (see the PyArrow documentation, it’s excellent.)

$ pip install pyarrow

.....

Here’s the Python/PyArrow/Pandas way of reading in the same Parquet data, producing a crosstab, and filtering by the appropriate TRANWORK and OCC2010 values:

import pandas as pd

import pyarrow as pa

import pyarrow.parquet as pq

table1 = pq.read_table('usa_00065.parquet', columns=['PERWT','YEAR', 'OCC2010', 'TRANWORK'],nthreads=4)

df = table1.to_pandas()

filtered = df[(df.YEAR==2016) & (df.TRANWORK>0)]

results=pd.crosstab((filtered.OCC2010>=1000) &(filtered.OCC2010<1100) ,

filtered.TRANWORK==40,

filtered.PERWT,

aggfunc=sum)

# print out or further process resulting cross-tab table

print results

Here you can see that the pyarrow.parquet library provides a to_pandas() method, which converts the parquet data to a Pandas dataframe. After that, the script is just pure Pandas, which may be familiar to any data scientist used to working in Python.

Timing this, we see it takes just a few seconds longer than the C++ version:

$ time python prog_bikers.py

TRANWORK False True

OCC2010

False 145593645 824999

True 3983940 36719

real 0m5.877s

user 0m0.590s

sys 0m1.120s

Not as good as the C++ and q combo, but pretty good. Part of the extra time is due to starting up Python itself. In general, the data reads should be just as fast as with a C++ program. Data read in from Parquet is stored using the Arrow in-memory data storage library mentioned above.

Converting to Parquet with Python

We have shown how we can tabulate Parquet data with Python, but we haven’t yet discussed how to convert other formats to Parquet with Python. It’s quite easy, though not as efficient as the custom C++ solution make-parquet in terms of memory required. You simply load a CSV into a Pandas data frame, then save the data frame as Parquet.

import pandas as pd

import pyarrow as pa

import pyarrow.parquet as pq

df = pd.read_csv('usa_00065.csv')

print "Loaded csv"

df.to_parquet('usa_00065.from_pyarrow.parquet', flavor='Spark')

We’ll call this convert_to_parquet.py.

The default behavior of this tiny script will be to load all the CSV data into a data frame and infer the types of each column before saving as Parquet, which is very handy but slightly expensive with respect to time and memory use. Optionally you can read the CSV in by chunks (at the risk of mis-typing some columns with a few edge cases.) See the Pandas user guide for more info about auto type inference.

Just to give you a notion of how fast Pandas + PyArrow can be:

$ time python convert_to_parquet.py

sys:1: DtypeWarning: Columns (58,76) have mixed types. Specify dtype option on import or set low_memory=False.

real 3m16.278s

user 1m27.734s

sys 1m29.703s

Notice the column type errors: This is a drawback of auto type inference. You can theoretically scan the entire CSV to get the types correct, but my computer ran out of RAM and swapped. I gave up after half an hour. Never fear though, if you’re serious about importing a particular schema you can specify all the column types explicitly when importing into Pandas and avoid this costly step.

If you’re comfortable with Pandas you could use a Pandas + PyArrow Python script as part of a data analysis pipeline, sending the results to GnuPlot as I showed earlier.

Finally, when reading Parquet with PyArrow you can use more than one thread to read columns and decompress their data in parallel:

table1 = pq.read_table('usa_00065.parquet',

nthreads=4,

columns=['PERWT','YEAR', 'OCC2010', 'TRANWORK'])

For especially large datasets this may provide some additional speedup.

Conclusion of Part 2

Thanks for sticking with this post to the end! I know that was a lot. Hopefully you found some useful content in there!

Although Parquet was originally developed for use with parallel processing frameworks like Hadoop and Spark, today we’ve seen how this handy columnar storage format can also make single-computer big data computation a lot faster and more scalable with a modest amount of code.

The tabulate_pq C++ utility and the Python PyArrow examples above are just proofs of concept. You could make something that supports more variables or adds in more powerful aggregate functions like medians – tabulate_pq only does sum(). And most importantly, these examples are all still just single-threaded programs, aside from the PyArrow multi-threaded read we just showed. Since all modern computers ship with multiple compute cores, multi-threaded approaches can unlock even more of the potential and performance of your little laptop or desktop to work on big data. We’ll explore that concept in Part 3 of this series.

Authored by Colin Davis

Code · Data

CSV Parquet C++ Python Spark Data Science